Foreign Body

Corps étranger

Having arrived in Strasbourg only recently, I spontaneously head toward the European Quarter. Located in the northwest of the city, it covers the Wacken, from the Orangerie to the Robertsau. The area of the city through which I am walking up and down is not all that well-known and gives me the impression that it is somewhat deserted by its own inhabitants. I only come across a few joggers and people out for a walk; in some places however, tourist buses are more numerous. What am I seeking in this rather bland part of town? Perhaps the same things I did in Brussels —another city where the European Parliament has its sessions, in the hope of finding again what I observed and felt a few years back during a research stay.

As I see them, these government quarters have something about them that speaks to us of another Europe, maybe not the one ordinary citizens had dreamed of though. The legitimacy of the European Union was supposed to be based on prosperity and fairness for all. Today, its citizens are called upon to make sacrifices to their standard of living while multinationals are thriving.

Landscape issues, urban issues, social issues play themselves out in those places. Their soulless contemporary architecture looks to me like it is disconnected from the rest of the city. These tall glass buildings, with their cold, rigid lines, seem to have been put there indiscriminately. In these concrete-covered areas, one can espy checkpoints, surveillance cameras, many walls and closed gates reminiscent of cells.

At the Ill Basin, the city is reflected on the mirroring walls of the Parliament building. Strangely enough, this urban silhouette appears to be reflecting another city, perhaps any city, just a city that looks like all the others, a generic city of sorts. Is it really Strasbourg we see in this distorting mirror?

In these places, the specifics of Strasbourg fade and give way to a disembodied urban space. On Rue de la Carpe Haute, the EDQM building stands in sharp contrast to the rustic quarters surrounding it; contemporary architecture jostles with old country houses in an odd stand-off.

On Rue du Levant, the European Court of Human Rights overlooks lowly little gardens. Its overwhelming, invasive presence is a jarring one, clashing with its surroundings. A little further on, on Boulevard Pierre Pflimlin, I am taken aback by its inordinate bulk in relation to the surrounding neighbourhoods. Near the entrance, the colours of the European Union fly. I take pictures of the reflections of these flags as they reverberate on it. To me, they look like they are caught within the building’s structure.

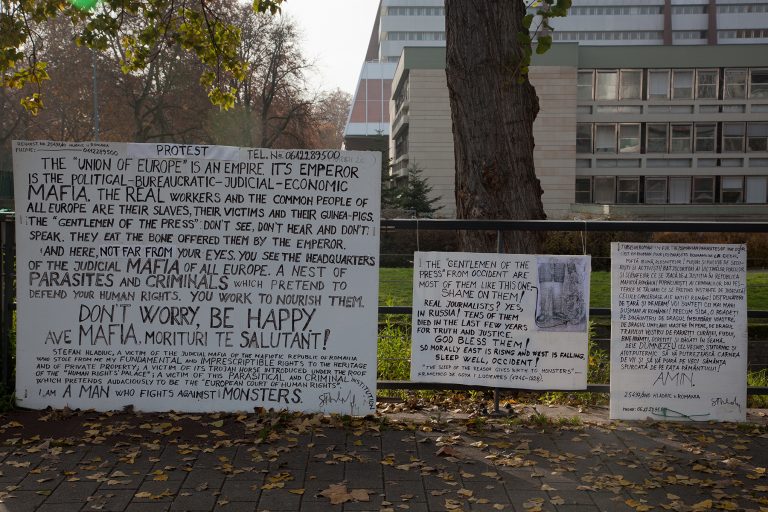

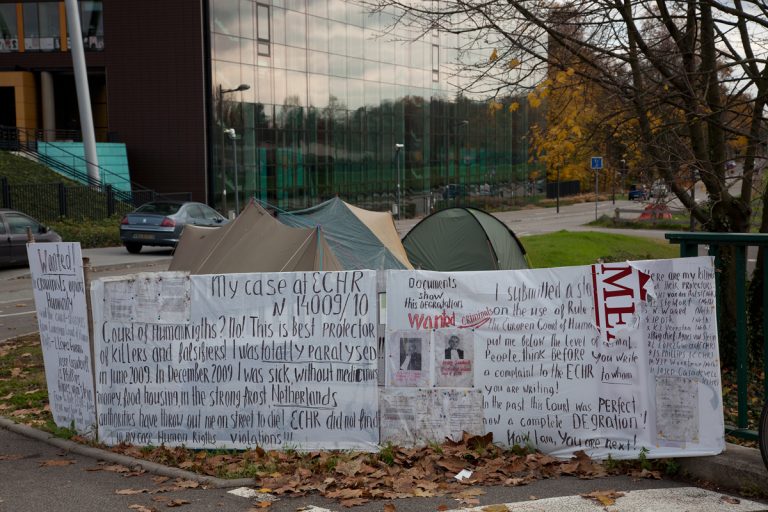

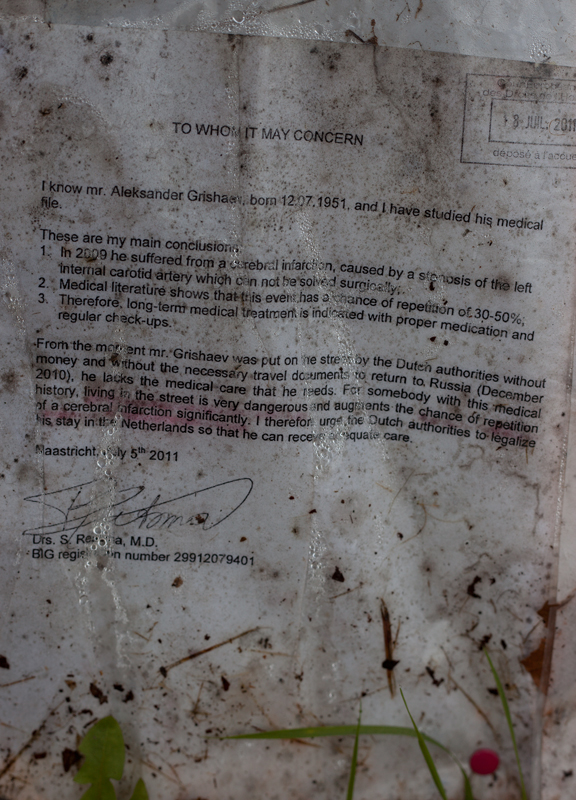

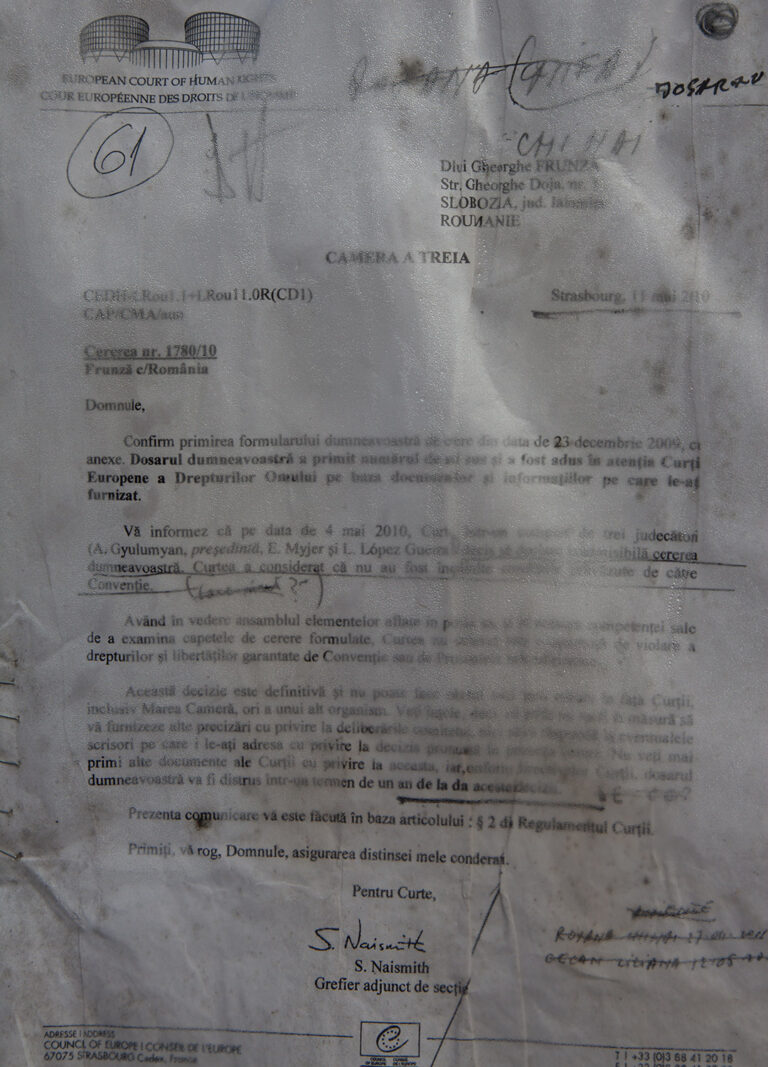

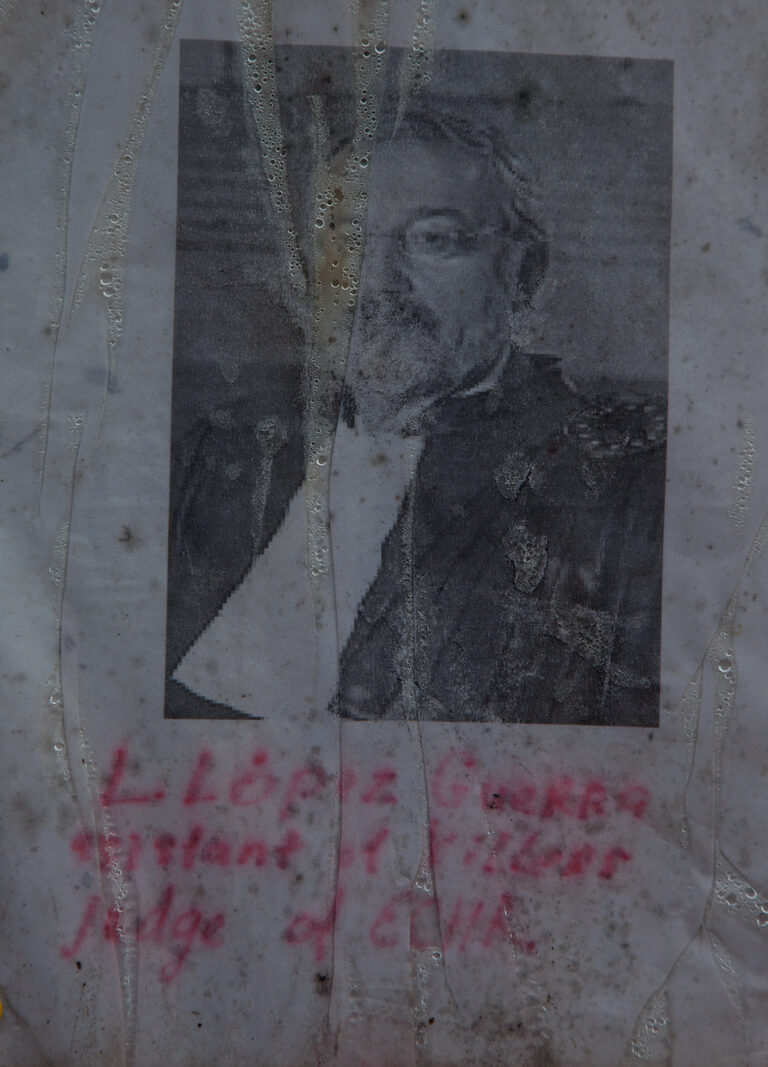

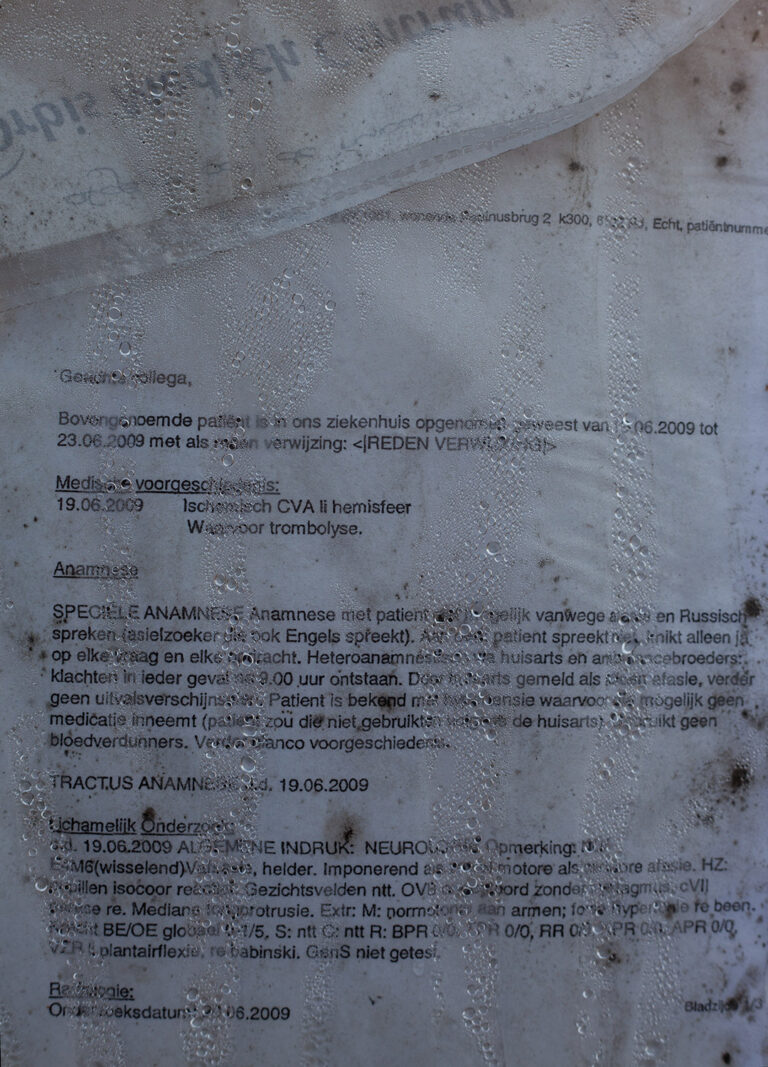

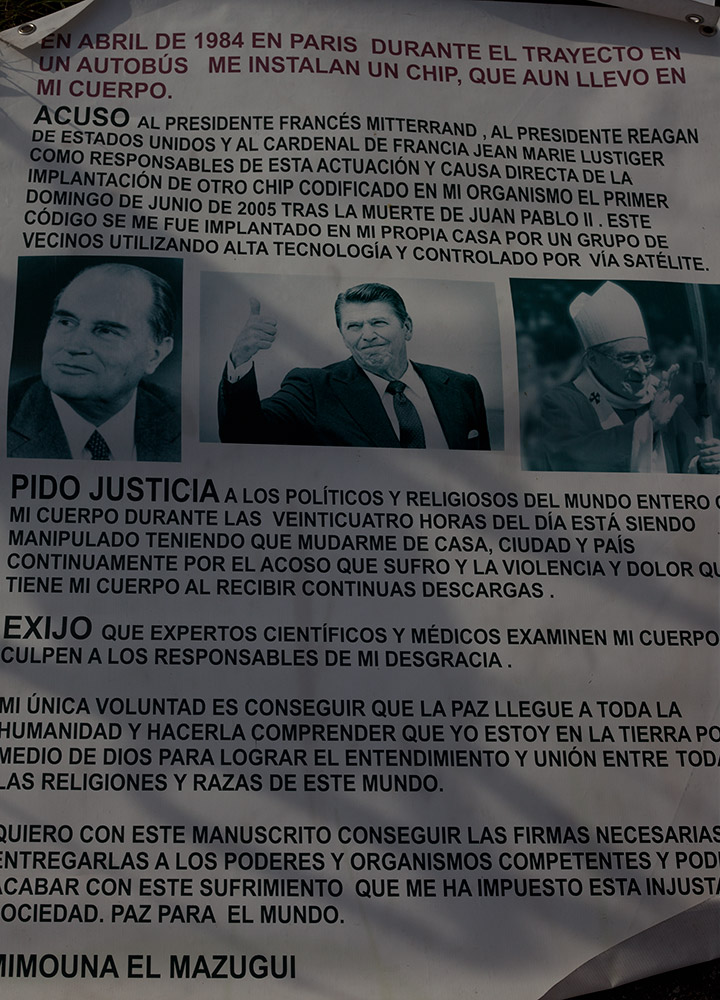

This public institution is the review body for tens of thousands of citizens each year. Some of them even camp right next to it in makeshift shelters. Protesting, waiting or ranting, they live there under the grey November sky. Be they unregularized migrants or mad citizens —some of them literally out of their minds, they all have different stories, which they attempt to tell me in a language I don’t understand. Their presence on these premises becomes for me a more general expression of disenchantment and indignation. They seem to be telling me another story: that of Europe’s deprived, of the marginalized of the global economy we know today.

Final day in Strasbourg. I am taking pictures of the sun’s reflections on the Agora’s glass walls. They mirror back to me an inverted day that looks more like night.

FRANÇAIS

Arrivée à Strasbourg depuis peu, je me dirige spontanément vers le Quartier des institutions européennes. Situé au Nord-Ouest de la ville, il couvre le Wacken, l’Orangerie et la Robertsau. Le secteur de la ville que j’arpente est plutôt méconnu et me parait relativement peu fréquenté par ses propres habitants; je n’y croise que quelques promeneurs et joggeurs. Par endroits, en revanche, les cars de touristes y sont assez nombreux. Que vais-je chercher en ce coin plutôt fade de la ville? Peut-être les mêmes choses qu’à Bruxelles, ville où le Parlement européen siège également – espérant y retrouver ce que j’ai observé et senti quelques années auparavant lors d’un séjour de recherche.

À mes yeux, dans ces quartiers officiels, quelque chose nous parle d’une autre Europe; peut-être pas celle dont les citoyens « ordinaires » rêvaient. La légitimité de l’Union européenne devait reposer sur l’équité et la prospérité pour tous. Aujourd’hui, le citoyen doit faire des sacrifices, racler le fond de ses tiroirs, tandis que les multinationales nagent dans les profits.

Des enjeux paysagers, urbains, sociaux se jouent en ces lieux solennels, dont les architectures sans âme paraissent déconnectées de la ville qu’elles habitent. Les lignes froides et rigides de ces grands édifices de verre semblent exprimer la brutalité de leur implantation. Dans ces zones bétonnées, on repère des postes de contrôle, des caméras de surveillance, beaucoup de murs et des grilles closes qui ressemblent à des cellules.

Au Bassin de l’Ill, la ville se réfléchit sur les parois miroitantes de l’édifice du Parlement. Cette silhouette urbaine semble curieusement refléter une autre ville, n’importe laquelle en fait; une ville semblable à toutes les autres, une ville… générique. Est-ce bien Strasbourg, dans ce miroir déformant?

Ici, la personnalité de Strasbourg s’efface pour laisser surgir un espace urbain désincarné. Rue de la Carpe haute, le bâtiment de la DEQM contraste fortement avec les quartiers bucoliques qui l’entourent; l’architecture contemporaine y côtoie de vieilles maisons pittoresques dans un singulier face-à-face. Je les photographie.

Rue du Levant, la Cour Européenne des Droits de l’Homme surplombe de modestes jardinets. Sa présence écrasante et envahissante jure, détonne. Un peu plus loin, boulevard Pierre Pflimlin, je suis déconcertée par sa taille démesurée en regard des faubourgs environnants. Près de l’entrée flottent les couleurs de l’UE. Les drapeaux s’y réverbèrent, comme captifs de la structure de l’édifice.

Chaque année, cette institution publique est une instance de recours pour des dizaines de milliers de citoyens. Certains d’entre eux campent d’ailleurs juste à côté, dans des abris de fortune. Protestant, attendant, délirant parfois, ils vivent là sous le ciel gris de novembre. Migrants sans papiers, citoyens en colère ou fous, chacun porte son histoire propre, qu’il tente de me confier dans une langue que je ne comprends pas. Leur présence en ces lieux devient pour moi l’expression générale d’un désenchantement, d’une indignation. Leur histoire commune est celle des déshérités, des laissés-pour-compte de cette économie globale que l’on nous fait miroiter comme miroitent les drapeaux dans les vitres.

Dernière journée à Strasbourg. Les reflets du soleil sur les parois vitrées de l’Agora me renvoient un jour inversé qui ressemble à la nuit.